Greek soldiers at the front during the Italo-Greek war

Anastasia Balezdrova

On 28 October, Greece celebrates its second most important national holiday known as OXI Day (NO Day - author's note.). Prime Minister at the time and dictator Ioannis Metaxas said no in response to the ultimatum by Italy to Athens under which it had to allow the Italian army to freely cross the Greek-Albanian border. The allies of Nazi Germany aimed at entering Greece to occupy strategic positions in Greek ports, airports and other locations, and to prepare for their further advance towards Africa.

Metaxas’ refusal was actually a declaration of war on the part of Greece. He responded to the Italian Ambassador to Athens, who presented him with the ultimatum, using the phrase "Alors, c'est la guerre" (This means war - author’s note).

Two hours later, the Italian army invaded the Epirus region and Greece officially was at war to protect itself from the invasion. The Italo-Greek war is divided into two parts. Only Greece and Italy waged war in the first part whereas the German, Italian and Bulgarian army that joined the war on 20 April 1941 occupied the country in the second part and divided it into three occupation zones.

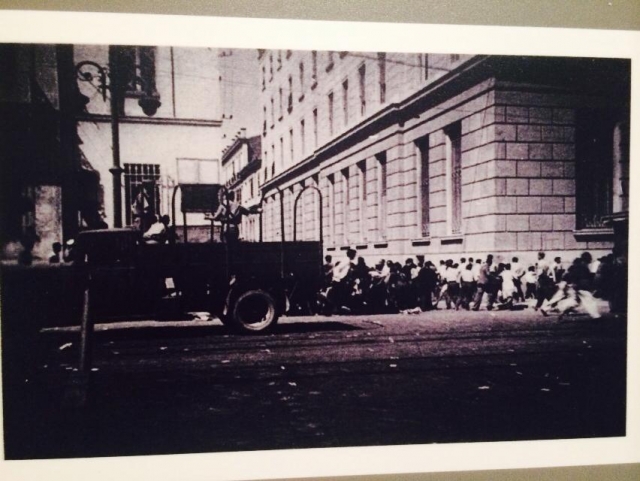

22 July 1943, German soldiers dispersed a peaceful demonstration in central Athens against the Bulgarian occupation of northern Greece, a photo from the exhibition "Athens during the years of German occupation" in the municipal gallery of Athens.

Athens was in the German zone of influence and one of the most painful memories of this period is the mass starvation of the population. According to historians, there were 40-45,000 victims of hunger in Athens in the autumn and winter of 1941-1942, although it is debatable if those who suffered from vitamin deficiency and lack of food and died from diseases could be considered victims of the Great Famine as well.

The situation in Athens was so severe that hundreds of dead bodies began to appear in the streets. They were loaded on wheelbarrows and buried in common graves, which is evidenced by the stories of witnesses of the events.

"Hunger, speculation. Properties were lost for a bottle of olive oil at that time. Things were so bad that some people were eating dog meat. They gathered the dead from the streets and brought them to cemetery N 3, where there was a common grave," residents of the Athens district of Kipseli told the members of the local group for collecting oral testimonies.

"Many people suffered from vitamin deficiency. I remember that I had swollen up, not to mention the childhood diseases that we suffered from without having access to medicines. There was cooked meat at home once, which had a strange scum and very unusual taste in general. Later we learnt that the bears that could be found in the woods near the neighbourhood of Pankrati before the war had disappeared. There was no wheat bread. I remember that some were selling bread made with carob flour," said a resident of the wealthy district of Kolonaki, continuing,

"No trade was carried out, only speculation. People paid for a few products with sovereigns and expensive jewelry. In Kolonaki the owners of a dairy and a bakery capitalized on food."

Food distribution in an Athenian street, Photo: Voula Papaioannou

This exploitation of Greeks by Greeks changed the map of their relationships. "My parents stopped greeting people who they knew before the war because they had grown rich during the occupation," said another witness. The same was true for Germany-friendly Greeks who became allies of the occupiers in many cases. "Before the war there were many and few after it. We stopped talking to them."

Witnesses from Kipseli state that the residents began to join the resistance organizations, mainly on the side of the Communist Party. They say they were the first to take action against hunger by creating the organization "National Solidarity". "In fact they gathered food from the countryside and obtained aid from international organizations, distributing it among residents in the fairest possible way. At that time, 1.5 million people lived in Athens and the total population of Greece was 7.5 million.

Nursing in the milk distribution centre, Athens 1942 - 1943, photo: Voula Papaioannou

The occupiers themselves were also concerned about starvation and its consequences, although they had imposed control over the production and trade of foodstuffs in order to prevent the supplies to the resistance organizations that had logistical support from the United Kingdom. Greek historians point out that, during the occupation, the Bulgarian authorities in northern Greece did not allow any distribution of food to the other two occupation zones where the large urban centres were located.

"As early as the month of May 1941 it became clear that the coming winter would be extremely difficult. The German deputy in Thessaloniki, Altenburg, informed on 7 May the German Foreign Minister and the government that starvation would acquire enormous proportions if the issue of food distribution were not resolved.

A discussion on the issue took place in Berlin but the answer was negative and the deputy was ordered to forget about any claims against Germany. It was impossible to obtain any supplies from the Soviet Union and for the German occupation zone that was the most populous to supply the Italian. In October the same year, Hitler assigned to Italy the responsibility for the livelihood of the Greek population. Mussolini replied, "Having taken even the shoe-laces of the Greeks Hitler is now expecting the Italians to feed them."

In September 1941, 10 thousand tons of grain arrived in Greece but the Italians said that no other aid would be sent. Starvation was tangible in the first week of October as stocks were very low. The Italians pressed the Bulgarian authorities who occupied the most fertile areas to send 100,000 tons of grain but they refused. The German pressure on them failed as well. Following the refusal of the Bulgarian army, the Italians sent 800 tons of grain and the Germans 10 thousand tons. However, the British army sank near the Greek coast the ship that was carrying them. The German deputy requested another shipment but it never arrived. Germany permanently solved the issue of food supply as late as the summer of 1942," George Zavakos writes in his publication in the magazine "History" entitled "Starvation in occupied Greece".

In their testimonies, the witnesses of the events told stories that were reminiscent of screenplays. "My father had begun to cooperate with a resistance organization and had hidden weapons inside the piano at home. One day, a German soldier knocked on our door while I was playing the piano. With gestures, he told my mother that he had heard me playing and wanted her to show him the piano. When he entered the room, I got up and he sat down and started playing. He played excellently, who knows what he was doing before being mobilized in the German army. Then he continued to come and play for several days and my mother stood frozen, fearing that he might open the piano lid and find the weapons hidden inside the piano. That did not happen and the soldier stopped coming. Perhaps he had been moved elsewhere," said one elderly woman from Kipseli.

Meanwhile the campaign against the Jewish population was underway too. "One day we woke up and all were gone. They were just gone. Days later, quite by chance, I saw one of our neighbours in another neighbourhood. She whispered, ‘Please do not tell that you saw me.’ They were afraid of the Germans," said the old woman.

Athens was free again on 12 October 1944 when the German army began to withdraw. The testimonies to the joy of residents are presented in a video by the 56th school in the Athens district of Ambelokipi.

"We were enthusiastic. The people carried the Greek national flag, rushing to Syntagma Square to celebrate the liberation," a resident of the neighbourhood told the interviewing students. Other residents described how they observed the withdrawal of the German army whereas others commented that the joy due to the end of the occupation lasted only for a short while because the December events in Athens were followed by the bloody civil war.

The interesting thing in this project is that it is the work of teachers and students, 83% of whom are from different nationalities. One of them is 14-year-old Boris Antchev from Bulgaria, who not only presented it but was also the cutting editor of the video.

"I like the story that we hear from the people interviewed, the preparations for the discussion and the subsequent work. Otherwise, I am not particularly a fan of history as a school subject," he told GRReporter.

Boris is interested in computers and his dream is to become a developer but he has an opinion about how we should perceive our common history, "In history there are good and bad moments, but we should keep the good ones and leave aside the bad."