Zdravkа Mihaylovа

for GRReporter exclusive

Odette Varon-Vassar is among the first Greek scholars who pointed out the significance of International Holocaust Remembrance (27 January). Тhis year the historian delivered an introductory lecture in Paris at an event on this occasion, co-organized by UNESCO and the Greek representative to the international educational cultural and scinetific organization. During the event, Ambassador of Greece to UNESCO Catherine Daskalaki delivered a welcoming address and the speech of Odette Varon-Vassard preceded the screening of the documentary Kisses to the Children (2011–2012), attended by its director Vassilis Loules. The film brings together the testimonies of survivors of the dramatic events during the Nazi occupation of Greece, who, being mere children at that time, were hiding with Greek Christian families. Many young people, who were taken out from the Nazi cordon and hidden in the countryside, survived during this period.

Professor of Modern History at Athens University Hagen Fleischer writes about the film, "The director did not seek to make another dramatic film about the Holocaust but wanted to focus on muted fear and isolation experienced by the children in conditions of extreme abnormality. The emotions of the viewer are not being extorted, the storytellers speak calmly, with immediacy and without any verbal excess. The courage of the people, of the Christians (not only of those who formally called themselves so) who risked their lives by hiding and helping these children is apparent. At the same time, the continuing decline of the Jewish communities in the country after the end of the Nazi occupation is implied too. Normality of life was gone, nothing was the same any longer. One of the female characters in the film, Rosina Pardo, explains, 'I am free of hatred already. I hate only the ones who try to imitate THOSE.' Rosina builds bridges. 'But not for those watching for an opportunity to destroy them. All of us must be on the alert.'"

The event in Paris, commemorating the victims, was under the general slogan borrowed from the title of a book by Odette Varon-Vassard, The Emergence of a Difficult Memory (published by Estia, Athens 2012). As noted in the UNESCO press release for the event, "The Nazi occupation of Greece was particularly brutal in the country and disastrous for its economy, not counting the 250,000 victims (of executions, deportations, death, hunger). The members of the numerous and thriving Jewish communities in northern Greece and in other areas of the country, namely from Central Greece to Crete (about 67,000) were deported and killed."

Odette Varon-Vassard (Athens, 1957) is a historian of contemporary history. She studied at the University of Athens and at the Institute of Modern Greek Studies at the University of Sorbonne (Paris IV). She has been teaching Greek history at the Hellenic Open University since 2001. In 2005 she was honored with the distinction of Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Minister of Culture (Chevalier de l’ordre des arts et des lettres).

Her research focuses on the '40s, starting with the illegal press ran by young people during the Occupation. Her first book was published by the Secretariat General for Youth (Greek Young Press 1941-1945. Recording, pub. IAEN, 2 vols, Athens 1987). Her second book, based on her doctoral thesis, is a study of how young people joined the Resistance in Greece (A Generation Matures - Young Men and Women in the Occupation and the Resistance, Hestia Publishers, Athens 2009). Her most recent research focuses on the genocide of European Jewry and its representations, on the cultural identity in the Jewish Diaspora and on concentration camp literature (The Emergence of a Difficult Memory. Essays for the Genocide of Jews, Hestia Publishers, Athens 2012, 230 p. (second ed. completed 2013, 260 p.)

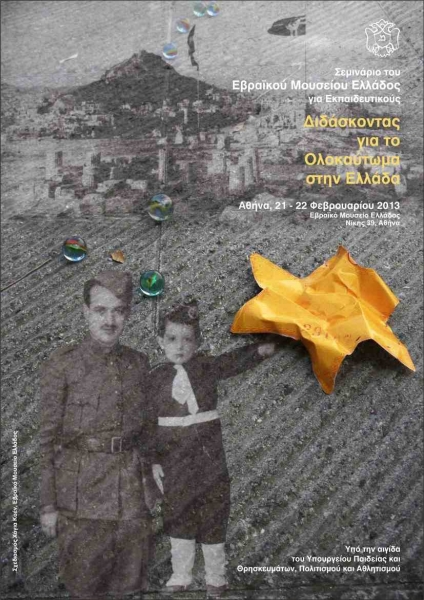

She is a member of The Society for the Study of Modern Hellenism Mnimon (since 1979) and was one of the founding members of the Society for the Study of Greek Jewry (Salonica 1990), playing an active role in the ‘90s. She has collaborated with the ‘Fondation Mémoire d' Auschwitz’ in Brussels and with the Faculty of Modern Greek Studies of the Strasbourg University. Recently, she has organized a seminar on concentration camp literature at the Jewish Museum of Greece (2011, 2012) and on the History and Memory of the Holocaust (2013, 2014). She participates also at the annual seminar of the Jewish Museum on “Teaching about the Holocaust in Greece” (since 2007).

As a translator of French literature in Greek, she has translated works of A. Duby, F. Braudel, G. Flaubert, J. Semprun, F. Lyotard, T. Todorov, D. Analis, Albert Cohen, with whose work she dealt in particular. She was editor and director of the Translation Journal Metafrassi (11 volumes, 1995-2007) and she is a member of the Editorial Board of the Journal Contemporary Issues (Synchrona Themata).

- The second edition of your book The Emergence of a Difficult Memory: Essays on the Jewish Genocide is about to be released. What brings together the nineteen essays in it, what is their connecting link and main thematic circle?

- Maybe the keywords are memory and oblivion. The memory of the genocide of the Jews gives rise to more heated discussions, a variety of approaches to the topic and disputes. Faced with the traumatic fact of the genocide of the Jews planned by the Nazis and carried out by them and their collaborators in civilized and Christian Europe in the heart of the twentieth century, from 1942 to 1945, historians, sociologists, politicians and scientists express their position and interpret in different ways issues that have been "unmentionable, unthinkable" for decades. It is clear that a multidisciplinary approach to this phenomenon is required today more than ever.

Memory and oblivion as regards the collectively experienced traumatic events have their own dialectic. Making the memory of the extermination of the Jews resurface, breaking the silence about the horrific events proves to be a difficult process, not only in Greece but also in the international historiography and the testimonies of survivors. I examine how their silence, from a certain point onwards, has crystallized in memory which, instead of fading away, reverses, becoming increasingly clearer. It does not gush out easily or fade away over time. The memory of this genocide, which seemed to have been forgotten for decades, is painfully re-emerging and being cultivated, and it is fighting in order to impose itself, something that it was able to achieve on the international horizon in the 1980s. The inclusion of this memory and its historicizing was not implied for any society or scientific community. I also analyze the first oral and written evidence of survivors of concentration camps in Europe as well as the place of Greece in the geography of belated resurgence of memory.

- The historiography of the genocide raises two main issues relating to the sources and objectivity.

- Let's start with the sources. Where could the sources on which a historian could rely to write the history of these events be? Could they be in the documents and records that the Nazis themselves had taken care to destroy? Along with the Jews, the aim was the elimination of all traces. Any written evidence of the destruction, elimination of the witnesses was provided by the system and the only permitted means of exit was "the chimney". All this was an important concern of the Nazi leadership in relation to the final solution to the “Jewish Question”. If some of the camps fell partly intact into the hands of the Allies it was only because the perpetrators had failed to eliminate the traces (in Auschwitz they destroyed the crematoria and the gas chambers at a feverish pace before emptying the camp of its prisoners, those anyway who were still able to walk in the "death march"). We should not forget that the intention of the Nazis was to run concentration camps on an industrial scale, their raw material being men, women and children, their product ash and by-product smoke. No living witnesses should have remained. Moreover, the information left by the perpetrators in surviving records is of a completely different kind, of bureaucratic nature. Contrary to their plans, fortunately, there are survivors. There was no other way than for the survivors to speak out and for historians to find a way to comprehend the enormity of what they were hearing.

- Let's start with the sources. Where could the sources on which a historian could rely to write the history of these events be? Could they be in the documents and records that the Nazis themselves had taken care to destroy? Along with the Jews, the aim was the elimination of all traces. Any written evidence of the destruction, elimination of the witnesses was provided by the system and the only permitted means of exit was "the chimney". All this was an important concern of the Nazi leadership in relation to the final solution to the “Jewish Question”. If some of the camps fell partly intact into the hands of the Allies it was only because the perpetrators had failed to eliminate the traces (in Auschwitz they destroyed the crematoria and the gas chambers at a feverish pace before emptying the camp of its prisoners, those anyway who were still able to walk in the "death march"). We should not forget that the intention of the Nazis was to run concentration camps on an industrial scale, their raw material being men, women and children, their product ash and by-product smoke. No living witnesses should have remained. Moreover, the information left by the perpetrators in surviving records is of a completely different kind, of bureaucratic nature. Contrary to their plans, fortunately, there are survivors. There was no other way than for the survivors to speak out and for historians to find a way to comprehend the enormity of what they were hearing.

- A particular importance during these events is attached to Thessaloniki, as the largest Jewish community that lived in Greece was deported from there. You examine the coverage of these events in the oral testimonies and stories of survivors as well as in historiography and literature.

- The biggest crime against the citizens of Thessaloniki was committed in 1943 by the Nazi occupiers of the city. Only the first act of the drama took place in the city itself, namely the bringing together of Thessaloniki Jews in a ghetto to facilitate their deportation to the death camps. The second and final act, the implementation of the "final solution" intended by the Nazis happened in the camps set up in Poland, and especially in Auschwitz-Birkenau. However, one of the main reasons for the Germans to refuse to cede Thessaloniki to their Italian allies was its numerous and significant Jewish community which was their prime objective. It was an evil irony of fate that in a city where there had never been ghettos, they were created just for the deportation of its inhabitants. In his book Salonica, City of Ghosts. Christians, Muslims and Jews, 1430-1950, historian Mark Mazower notes that the third ghetto, that of Baron Hirsch, which had one exit straight to the railway station, was established in the late nineteenth century as a settlement to accommodate and shelter Ashkenazi Jewish refugees, survivors of the pogroms in Tsarist Russia.

- Seven of the texts in your book treat the issue of the deportation and extermination of Greek Jews. Your essay "The deportation of Jews from Thessaloniki: a crime without a trace?" uses as a motto verses by famous Greek poet of the first post-war generation, Manolis Anagnostakis, "All those human figures becoming again numbers/How am I to explain more plainly who were Ilias, Raoul, Claire, and how so many personalities became numbers?"

- Seven of the texts in your book treat the issue of the deportation and extermination of Greek Jews. Your essay "The deportation of Jews from Thessaloniki: a crime without a trace?" uses as a motto verses by famous Greek poet of the first post-war generation, Manolis Anagnostakis, "All those human figures becoming again numbers/How am I to explain more plainly who were Ilias, Raoul, Claire, and how so many personalities became numbers?"

- It is about the greatest mass murder of Thessaloniki citizens that has ever happened (1943–1944), elsewhere (in Auschwitz), with some victims who were ‘the other’ (Jews were different for the Orthodox, Greek-speaking national element), its perpetrators being some foreigners (the German invaders). Do the mentioned parameters justify the exclusion of that crime from the history of the city? This was the position of the city council in the summer of 2008 when it refused to include Thessaloniki in the Network of Martyr Cities and Villages of Greece. One argument was that the extermination of 96% of Jews from Thessaloniki (the actual percentage is 96%) would not turn the city of Thessaloniki into a martyr, as the offence "was committed outside Thessaloniki!" Approximately 50,000 Thessaloniki Jews perished, they were killed "elsewhere", which is why this event is not part of the city's history. The second argument was that Jews had inhabited the city "just" for five hundred years! In addition to the historical mistake, because these five-hundred years of existence refer to the Sephardic community, i.e. Hispanic Jews, whereas Jews had lived in the city since the first century AD, this argument is absolutely untenable since it is clear that less than five hundred years are more than enough for a proactive community (and the largest one in the city for many centuries) to leave its mark on the history of the city. Therefore, Thessaloniki missed not only the chance of joining the Network of Martyr Cities and Villages of Greece but mainly the opportunity of self-awareness, thus perpetuating a systematic oblivion. Ghosts unfortunately remained ghosts instead of actually becoming the past and a past trauma.

- You examine in detail the issue of the identity of the Sephardic Jews of Thessaloniki and of identities in general in the text "A journey dedicated to Sephardic Jews of Thessaloniki", which is about the book "Memories of a Life and a World" by long-time president of the Israelite community in the city Andreas Shephiha, edited by experienced journalist Sofia Pakalidou. How are policies changing to highlight the multicultural aspect of this city?

- The Jew was par excellence "the other, the different one" and the Greek national narrative did not include Jews up to the 1980s. These publications and discussions have become more frequent since the 1990s. The Resistance, the Civil War, the main historical trauma of Greek society were also taboo topics. I explore these issues elsewhere in my book "Youth in the Maelstrom of Occupied Greece" (published by Estia, 2008). I wonder how much more could the extermination of a national element (a bearer of an absolutely particular culture, namely the Sephardic one) that had inhabited a city and comprised the most populous and vibrant part of its population for 450 years (from 1492, the year of its expulsion from Spain to 1943 when it was deported by the Nazis) mark the history of this city? The part that had reinvigorated the Ottoman city deserted in the early sixteenth century to turn it into "Madre de Israel", "Jerusalem of the Balkans" and make the Sephardic culture shine not only in the western but also in the eastern end of the Mediterranean, and of course, deep down in the Balkan hinterland. So the 16th-17th centuries became the golden age of Thessaloniki Jewry, but of the city too, as it was its strongest ethnic element. The crime had left multiple traces on the body of the city itself.

Things are changing, however. The events that took place last March in Thessaloniki, under the auspices of the Municipality and upon the initiative of Mayor Yiannis Boutaris, on the occasion of the seventieth anniversary of the sending of the first group of 2000 Greek Jews to Auschwitz show that different wind is blowing. This will further open our collective memory and our society will gain self-awareness as well as new acute sensitiveness against all forms of racism. It is because the memory of the genocide of Jews in Europe is still, and must remain, emblematic of all victims of racism.

- What is the broader thematic range of the book?

- The memory-oblivion connection as well as that between silence and writing are explored both in the word of witnesses and in the texts of camp literature, e.g. primarily the works by Primo Levi and Jorge Semprun. Other texts treat issues such as the reconstruction of the events based on testimonies and camp literature, the denial of the Holocaust, the historiography of the genocide. The issue of revisionism that denies it refer to the approach of Pierre Vidal-Naquet and other researchers, and in relation to the issue of memory the views of Tzvetan Todorov are cited. The most recent texts refer to the institutionalization of memory through places of memory, museums (in a separate text about the issues of the Holocaust museums), monuments and anniversaries (27 January, the International Holocaust Remembrance Day). Therefore, the approach to the event is multi-dimensional and is directed towards its historicizing.

The deportation of Greek Jewish communities is also analyzed. In addition to the populous Sephardic community in Thessaloniki, there were twenty-five Jewish communities in the early Nazi occupation of Greece. The rate of extermination in Greece was very high, 83%, and it reached 96% in Thessaloniki, where the Jewish community was almost erased; today it numbers 3,500-4,000 people, in total the survivors from Greece are about 10,000. Some towns, especially in northern Greece, have no remaining community but in recent years, on the initiative of municipalities, they have placed monuments of the Holocaust, for example Komotini, Didymotiho, Volos and Rhodes as well. I think that the designation of the area is important as well as its connection to a past that is already perceived as the past of the whole city instead of its destroyed community alone.

On 11 July 1942, the day known as "Black Saturday", thousands of Jews were forcibly gathered, in unbearable heat, in Eleftherias Square in Thessaloniki and subjected to harassment and humiliation by the Nazis. Quite reasonably the monument of Jewish martyrs in the city was placed right there. However, dozens of cars parked in the open parking lot, which the square has become nowadays, are hiding the monument that is visible only at close range. The car park should be removed from there so that the space can be formed in a different way. The square could be renamed "Deportation" Square instead of the present "Freedom" Square. However, things are progressing. Since 2010, Athens has also had its monument to the victims of the Jewish genocide (in Thiseio district, corner Ermou and Efvoulou streets). The beams that are separated from the main body of the marble Star of David contain the names of the Greek cities that lost their Jewish communities. Significantly, the area for placing it near the synagogue was provided by Athens municipality.

- The cover of The Emergence of a Difficult Memory is illustrated with a photo of Albert Cohen’s native house, a Greek Jew born on the island of Kerkyra (Corfu), who later became famous as a French-Swiss writer. "The Jewish community on Corfu was almost completely destroyed, as against the marvellous exception (in Greece) of the complete salvation of the Jews on nearby Zakynthos” you write. When did the sensitivity of Greek writers awaken and how was the theme of fate and of the extermination of Jews transferred into the post-war Greek literature?

- In the 1970s, two novels relating to the deportation and extermination were published, both by Thessaloniki authors. Psychiatrist Nikos Kokantzis published "Gioconda" with the tag-line "The following story is true." The story is about his first adolescent romance in the years of occupation with a Jewish girl who lives next door, Gioconda. She and her family will be deported from Thessaloniki and he will not see her again. In addition to the compelling love story, the book is the strongest text relating to the persecutions against Jews, in terms of the description of both their forcible gathering in Eleftherias Square in July 1942 and the farewell between the two neighbouring families.

In "Telephone Centre" by Nina Kokkalidou-Nachmia, Miriam will be deported to Auschwitz. We follow her captivity through the letters she sends, in her thoughts, to her girlfriend. Miriam is one of those who resist inside the camp and takes part in the revolt of Greek camp inmates who work in the crematoria. Both the story of the relationship between Jews and Christians in a harmonic framework and the approach to the genocide are of particular interest in this book.

Two other shorter texts are equally emblematic. "The Bed" by Thessaloniki novel writer Yorgos Ioannou focuses on what has been left behind of his friend from childhood, and perhaps his first erotic partner, namely his friend’s bed. When the neighbouring Jewish family is deported, their house is violently robbed and only Iso’s bed remains in it. The narrator takes it to his house and spends the rest of the occupation sleeping in it, remembering his lost friend. Ioannou describes the persecution of Jews from Thessaloniki, offering a first chronicle of the developments.

Vassilis Vassilikos’ short story "My friend Ino" focusses on the issue of Jewish property and it talks about the Greek collaborators who benefited from the abandoned Jewish possessions. It addresses the issue of unpunished guilt, which is still hanging over the whole of society. He explores the experience of camp inmates through the testimony of survivors. The examples may be few, but they are typical. The sensitivity of the Greek writers has already awakened.

- The memory of the Holocaust began to be impressed upon the collective memory of the West and internationally in the 1980s, with Auschwitz becoming the metonym for genocide. The survivors have begun writing about the Holocaust en masse since the 1980s. When was the moment for the verbal expression of these painful memories ripe in Greece, when was the first evidence of surviving Greek Jews published and which are the most typical among them?

- The first evidence, that by Heinz Kounio "A Litre of Soup and Sixty Grams of Bread: The Diary of Prisoner Number 109565" was published in Thessaloniki in 1982, then Pavlos Simha published "The Dimitriou Family" (Thessaloniki, 1988). A literary magazine in Athens published a memoir text by Sam Profeta "Thessaloniki-Auschwitz". At the end of the decade, Berry Nachmia’s testimony "A Cry for Tomorrow" was published in Athens, which has a multi-dimensional significance. The 1990s witnessed a "boom" of interest in this subject in Greece. Here I must mention the work by authors Errica Kounio-Amarilio and Albertos Nar Oral Testimonies of Thessaloniki Jews on the Holocaust, edited by professor at Thessaloniki University Frangiski Abadzopoulou (Thessaloniki 1998). Also the book by Errica Kounio-Amarilio 50 Years Later – Memories of a Thessaloniki Jewess, again edited by Abadzopoulou. The book has been translated into English, French, German and other languages. I want to emphasize the importance of translation. A Greek testimony "speaks out" in European languages, reminding the West of the fact that the Nazi persecutions were not confined to Central and Eastern Europe but reached the Aegean coast and our sun-bathed islands and ports. I am mentioning this because foreign publications, museums and congresses that claim to provide a comprehensive look at the genocide of Jews often forget or underestimate this fact. This means that the case of Greece is often totally absent or its mention is totally disproportionate to the scale of the persecution as just a few words present the experience of Thessaloniki. I believe that this "silence", another silence oppressing the genocide of Jews, is associated with the Sephardic origin of the majority of them. In the minds of Jews in the West, the Holocaust is too often considered as a case of Central and Eastern Europe. Poland, Hungary, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria undoubtedly are the countries that paid the heaviest blood tax. Concerning Ashkenazi Jews, Yiddish being their common language, the genocide is often considered a phenomenon relating to them alone. This is the reason for the importance of the translation of the Greek Jewish testimony.

- The first evidence, that by Heinz Kounio "A Litre of Soup and Sixty Grams of Bread: The Diary of Prisoner Number 109565" was published in Thessaloniki in 1982, then Pavlos Simha published "The Dimitriou Family" (Thessaloniki, 1988). A literary magazine in Athens published a memoir text by Sam Profeta "Thessaloniki-Auschwitz". At the end of the decade, Berry Nachmia’s testimony "A Cry for Tomorrow" was published in Athens, which has a multi-dimensional significance. The 1990s witnessed a "boom" of interest in this subject in Greece. Here I must mention the work by authors Errica Kounio-Amarilio and Albertos Nar Oral Testimonies of Thessaloniki Jews on the Holocaust, edited by professor at Thessaloniki University Frangiski Abadzopoulou (Thessaloniki 1998). Also the book by Errica Kounio-Amarilio 50 Years Later – Memories of a Thessaloniki Jewess, again edited by Abadzopoulou. The book has been translated into English, French, German and other languages. I want to emphasize the importance of translation. A Greek testimony "speaks out" in European languages, reminding the West of the fact that the Nazi persecutions were not confined to Central and Eastern Europe but reached the Aegean coast and our sun-bathed islands and ports. I am mentioning this because foreign publications, museums and congresses that claim to provide a comprehensive look at the genocide of Jews often forget or underestimate this fact. This means that the case of Greece is often totally absent or its mention is totally disproportionate to the scale of the persecution as just a few words present the experience of Thessaloniki. I believe that this "silence", another silence oppressing the genocide of Jews, is associated with the Sephardic origin of the majority of them. In the minds of Jews in the West, the Holocaust is too often considered as a case of Central and Eastern Europe. Poland, Hungary, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria undoubtedly are the countries that paid the heaviest blood tax. Concerning Ashkenazi Jews, Yiddish being their common language, the genocide is often considered a phenomenon relating to them alone. This is the reason for the importance of the translation of the Greek Jewish testimony.

In 1994, a special edition of Synchrona themata magazine was devoted to the issue, and important books were translated in the following years, including Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950 by Mark Mazower (published by Alexandria, Athens 2007) and Crown and Swastika. Greece during the Occupation and Resistance 1941–1944 by Hagen Fleischer (published by Papazisis, 1995), containing chapters on the Holocaust of Greek Jews. Thus, around 1995, a bibliography first began to form.

- How would you respond to those who believe that "The Diary of Anne Frank" is a literary mystification and that the genocide of Jews never existed, nor did its symbolic tool, the gas chambers?

- It must be emphasized from the outset that there can only be different interpretations in terms of the issue of genocide, without insinuations about the fact itself. There is no room for "views and opinions", the fact itself is not subject to discussions, this just happened. Nevertheless, during the 1980s which were favourable yeas for the revival of racism in Western Europe in parallel with the collapse of memory regarding the Holocaust, untenable theories were born that denied the existence of extermination camps and hence the implementation of the genocide of the Jews. This was the decade the end of which would be marked by the collapse of real socialism, mass emigration and a revival of nationalisms. All of these events would contribute towards the adoption of such theories. The fact that all that was dressed in the form of scientific views that were spread like well-established scientific knowledge (publications, lectures, conferences, etc.) spreads turned out to be even more dangerous. Later, in the 1990s and even in the first decade of the 21st century, the uncontrolled possibilities offered by the Internet provided the opportunity for even greater dissemination of these lies.

This course, which was initially characterized as revisionist and later as negativism, in Germany took the form of the famous dispute between historians, called Historikerstreit. Unfortunately, an established historian by the time, namely Ernst Nolte, became the leader of the German "revisionists". By the way, Nolte denied this special feature of the genocide and implied that the victims and the executioners were equally responsible. He also argued that the Nazis had copied their practices from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and therefore Nazism was simply the necessary response to communism. Finally, he argued that the only innovation of this genocide was the invention of the gas chambers.

Englishman David Irving who supported similar views was brought to trial and was convicted. In France, where collaborationism and the cooperation of the government in Vichy were concealed for years, these theories were pointed out by less serious representatives such as Robert Faurisson and Paul Rassinier, but also by former Marxist Roger Garaudy. The extreme left intersected with the extreme right. Faurisson, who unlike Nolte, denied the very existence of the gas chambers, was soon expelled from the University of Lyon and the first texts that deconstructed this forgery were written by Nadine Fresco and Pierre Vidal-Naquet ("A Paper Eichmann", "Assassins of Memory"). In his extremely important texts Pierre Vidal-Naquet (known in Greece for his works, commenting on history, philosophy and mythology of ancient Hellas) deconstructs the arguments of Holocaust deniers, showing the mechanism of constructing a lie. Later France voted laws banning the expression of such views (the first of them being the Gayssot law) and prohibiting their publication and dissemination. There has been a wide discussion on the functionality of these laws (which were then multiplied) as well as a challenge on the part of the community of historians who are worried about their canonical functioning.

The last text by Primo Levi published in "La Stampa" newspaper just three months before his suicide, entitled "The Black Hole of Auschwitz" (the one that ultimately engulfed him) is dedicated to the anxiety caused by these ideas and, of course, to the relevance that they conceal and the purposes they serve.

- In one of your studies "Problems of the Museums of the Genocide and the Resistance Movement: the European and American Model" you draw parallels between the similarities and differences in the approach to the preservation of memory in Europe and overseas. Which are the main conclusions in this comparison?

- The differences are due to the mentality dominant in the creation of museums. I mean the major museums in the United States that opened their doors almost simultaneously in the spring of 1993, namely the Museum of Tolerance/Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles and the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. American museums tend to evoke a burst of emotions by reconstructing the tragedy, leaving open the wound in those who carry the memories but mostly provoking an emotional shock that will open a new "wound" in those who now learn for the first time, in those who were born after the war. The methods they use aim to make the visit memorable, through dialogues carried out with the help of multimedia devices. This purely American experience involves a spacious room with lots of TV screens connected to a CD-ROM with which the visitor communicates, asking questions on the topic of racism in contemporary California society and receiving answers to them. It is natural for the phenomena of racism and xenophobia to engage a par-excellence multinational society in which white American citizens make up only 40% of the population.

On the other hand, it seems that a different mentality prevails outside America, such as that of the younger staff at Yad Vashem and at the French museum I have in mind, "Centre de Résistance et de Déportation" in Lyon (Resistance and Deportation History Centre), which today is one of the most modern museums in Europe dealing with this era. However, a typical feature of it is the fact that it is called a centre instead of a museum as it is engaged in research work. It is considered that the Resistance and Deportation History Centre in Lyon is representative not only of the French but also of the broader European concept of the subject. The Centre is equally aimed at adolescents who must now learn, to people who have memories of that time and want to remember but also to researchers and historians. It achieves popularisation that does not detract from the nuances and usually avoids the pitfalls of simplistic and Manichean rhetoric. Let us briefly recall the specific importance of the city in the French history of the Resistance, which explains why such a museum has appeared there. Lyon was a metropolis in the southern zone, where the French Resistance found refuge: in short, we are talking about the capital of the Resistance. On the one hand, the city of Jean Moulin (1899-1943), an emblematic figure in the French Resistance, and on the other, a city where senior Nazi Klaus Barbie acted along with others. Moreover, the notorious trial of Klaus Barbie, who was responsible for the deportation of the Jewish community of Lyon, took place there in 1987. Last but not least, during the 1980s, Lyon also became the cradle of French revisionism, of the "theory" that denies the genocide of Jews, as the person who introduced it in France, Robert Faurisson, was teaching at the local university before being excluded from the university community. So, in this environment with increased sensitivity, the Centre plays a role in response to revisionism as well, by being a continuous, symbolic projection of the Barbie trial.

It could be said that American museums primarily aim to provoke an emotional shock whereas the Centre in Lyon aims more towards understanding through intellect. The emerging discrepancies are a product of a different historiographical approach as well. When it comes to the years 1941–1945, American museums mainly address the deportation and genocide (which the American terminology calls the Holocaust, a term that the non-English speaking historiography does not accept, as in terms of the Old Testament it means a "whole burnt offering", i.e. a voluntary sacrifice through burning, and it rightly adopts the symbolic concept of Auschwitz, genocide or Shoah). This different historiographical approach does not treat the resistance in different European countries as well as other aspects of World War II, they remain distant, alien and ultimately of no interest. The appearance of the European context, the real space where the drama unfolded, here collapsed and faded. For these museums, the subject of interest in this historical period is the very Jewish tragedy.

In any case, the 1990s were the time when American society first awakened to the issue of genocide and it seems that it has already affected it. Another example of the mature interest is the USC Shoah Foundation which has been recently established in Los Angeles and which has been proceeding, at a fast pace, in the collection of oral testimonies of thousands of surviving Jews from all over the world in order to create the largest archive of audio-visual testimonies of survivors. The testimonies of ‘thousands’ of Greek Jews from Athens, Thessaloniki and from smaller cities were included in the programme of the Foundation in 1997–1998.

- In your opinion, which one of the two types of museums has a more powerful influence and the visit to which one remains more memorable?

- I raise the question without answering it: which type of museum ultimately serves better the cause of preservation and handing down the memory of these events? Should a museum dedicated to this period influence the emotions so strongly? Is the dramatized way the most effective one in order for such a space to touch the visitor today? However, since there is a kind of "European scientific snobbery" which refers to "Americanizing the genocide" in a more insidious and arrogant way, I would not like to leave the impression that I personally share it when commenting on these museums. I just want these observations to be a starting point for a critical reflection on the issue.

- I raise the question without answering it: which type of museum ultimately serves better the cause of preservation and handing down the memory of these events? Should a museum dedicated to this period influence the emotions so strongly? Is the dramatized way the most effective one in order for such a space to touch the visitor today? However, since there is a kind of "European scientific snobbery" which refers to "Americanizing the genocide" in a more insidious and arrogant way, I would not like to leave the impression that I personally share it when commenting on these museums. I just want these observations to be a starting point for a critical reflection on the issue.

Is the answer unequivocal or does every society ultimately create the type of museum that best fits its needs? Is the "aggressiveness" of American museums (especially the one in Washington) about to overwhelm the visitor, taking the risk of giving the opposite result, namely to make the visitor leave wanting to forget about this horrible thing as soon as possible? On the other hand, how can a museum manage to send the message to people the great majority of whom, such as the hundreds of thousands of young people of Asian and Mexican origin in Los Angeles and younger Americans in general, do not have the faintest idea of the events, as they lack the sensitivity of the Europeans on this issue? Wouldn’t a "discreet" museum where the visitor has to spend much time reading and reflecting be a complete failure in this society, which is the quintessence of spectacularity and consumerism? The issue is very complex and I will leave it open.

- The epilogue in your book entitled "A Day in Memory of the Genocide of European Jews" uses as a motto Elie Wiesel’s words, "The executioner always kills twice, the second time through silence." Why has 27 January been preferred for the International Holocaust Remembrance Day?

- On 27 January 1945, while advancing through Poland, parts of the Red Army found Auschwitz without searching for it or aiming to liberate it since the liberation of the camps was not among the immediate objectives of the Allies. The Germans had emptied the camp a few days earlier, driving 58,000 prisoners before them on a "death march". Seven thousand prisoners in poor condition, wandering like ghosts and seeking nonexistent scarce food, had been left in the camp. One of them was Primo Levi, the witness par excellence of Auschwitz and the author of a humanist trilogy, Part One entitled If This is a Man. Hundreds of thousands of people died in the camp while it was functioning, finding their grave "in the air" as wrote poet Paul Celan, another person who later committed suicide like Primo Levi, and both being survivors of the death camps.

If the date of the liberation of this camp is recognized by the United Nations as "International Holocaust Remembrance Day and Prevention of Crimes against Humanity," it is because the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau killed 960,000 Jews. This is the highest number corresponding to only one camp and it comprises approximately one-fifth of the total number of Jews (5.66 million) exterminated in the genocide organized by the Third Reich. 21,000 Gypsies, 75,000 Polish Catholics involved in the Resistance, 15,000 Soviet captives and 15,000 captives from other European countries were killed in the same camp, for "purity of race". Of the 960,000 Jews, 60,000 were Greek Jews, a figure that increases the percentage of extermination to 82% of the pre-war number of the community. Thessaloniki’s share was the largest, 50,000 victims, as its numerous community with its long-lasting history and brilliance was exterminated almost to a man. Over 90% of some other communities, such as all those in northern Greece, but also in Rhodes and Kerkyra, were exterminated too. In other words, Greece has every reason to honour this anniversary.

- What is the symbolic meaning of this commemoration?

- On the one hand, it is institutionalized and it is another issue whether it is known and put to a useful purpose. It is no coincidence that the anniversary was established by the European Ministers of Education in 2002 and adopted by the UN in 2005 and, with regard to Auschwitz, it is a World Heritage Monument recognized by UNESCO. The International Holocaust Remembrance Day has a quite clear pedagogical nature that is open to the public. The trauma is not only Jewish, it is not only the Germans’ fault, the tragedy happened in the heart of Europe, its episodes took place in every major European city, i.e. this is a page of European history and it concerns every European citizen of the present day and above all of tomorrow.

Reflecting on "the Holocaust" (in the way in which the public was aware of it and accepted it as a cultural trauma, i.e. from the beginning of the 1980s and later) should occupy a central place in our minds of European citizens, not only as an extermination of millions of people and civilisational catastrophe but also as an extreme attempt of renouncing human nature, which did not only kill millions of people but literally deprived them of their human identity simply because of their origin. 27 January commemorates not only the victims of the Jewish "Holocaust", this day is emblematic of all victims of racism and singling out. In this sense, it is more relevant than ever, as new forms of racism and anti-Semitism are rising in Europe in the twenty-first century.

- How long has Greece marked this anniversary?

The International Holocaust Remembrance Day was relatively quickly introduced in Greece. The first ceremony took place in January 2004 on the initiative of then-Foreign Minister George Papandreou. Since then, different events co-organized by the regional government of Athens and the official Jewish organizations have taken place each year. These include the laying of a wreath at the new monument of the genocide in Athens, which happened in 2012 for the first time. I think this is certainly a big step, which demonstrates the adoption of this memory and its inclusion in the national collective memory on the part of the state. The question is if that day, which, by no coincidence, was enacted by the European Ministers of Education, is valued in the educational system, how is the Holocaust taught in the schools, and if it is leading to a wider opening to the public. This is not a day of Jewish mourning (such as 11 April, the anniversary of the uprising in the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw), but a day of reflection and awareness on the part of the general public.