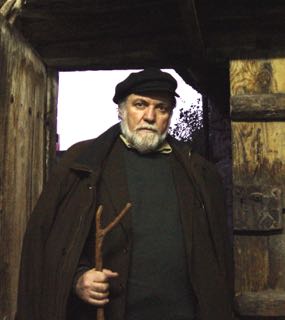

Photos: Michalis Pieris' personal archive

The Bulgarian edition of selected poems by Cyprus’ poet Michalis Pieris "Metamorphoses of Cities" (ed. 'Foundation for Bulgarian Literature', series 'Aquarium Mediterranean', Sofia 2015) had its première in Nicosia. The cultural event took place on the initiative of the Embassy of Bulgaria in Cyprus. Poems from the edition were voiced in Bulgarian and Greek in the presence of the poet and his translator into the Bulgarian language Zdravka Mihaylova, being simultaneously displayed in English (from the upcoming edition of his poetry in Australia, translated by Irena Yoanidi).

Why "Metamorphosis of Cities"? Michalis Pieris has always travelled and lived in Australia and Greece. The poet says that he "enters an unfamiliar city as one descends into a well and smells scents that rise from the earth. Every city has its own smell that emanates from its monuments, shops, its people, especially its women. I wander the streets like a man who is lost, looking for landmarks, watching people and objects as if seeing their type and shape for the first time, I see the smell while moving around me, looking to find the image that always remains the same. A female deity, a fairy that is slipping into the dwelling of the city, disappearing like a wild animal in the mountains with the confidence of her beautiful shape, with the arrogance of what is well put on the city fresco."

Born in Cyprus in 1952, Michalis Pieris is a poet, translator and university professor. He studied philology and theatre in Thessaloniki and Sydney (Australia), he has worked in universities and research centres in Greece, Europe, America and Australia. He has published short stories, theatrical works as well as research on the medieval, Renaissance and Modern Greek literature. He has published ten books of poetry, translated foreign poetry and ancient Greek drama.

Born in Cyprus in 1952, Michalis Pieris is a poet, translator and university professor. He studied philology and theatre in Thessaloniki and Sydney (Australia), he has worked in universities and research centres in Greece, Europe, America and Australia. He has published short stories, theatrical works as well as research on the medieval, Renaissance and Modern Greek literature. He has published ten books of poetry, translated foreign poetry and ancient Greek drama.

He is the founder of the Theatrical Workshop at the University of Sydney (1979) and the Theatrical Workshop at the University of Cyprus (1997), he has adapted for stage medieval and Renaissance literature works and has directed them, including the medieval "Cyprus Chronicle" by Leontios Machairas and the Renaissance masterpiece of Cretan literature "Erotokritos" by Vitsentzos Kornaros. Since 1993, he has taught poetry and theatre at the University of Cyprus.

He has been awarded many times for poetry, both in Cyprus and internationally: the International Poetry Award "Lazio Between Europe and the Mediterranean" (2009) of the Lazio region in Italy, the highest award of the Republic of Cyprus (2010) for lifetime contribution to Greek literature, the Medal of the Italian Republic (2011) for his contribution to promoting Italian culture in Cyprus and to the development of cultural relations between the two countries and much more.

GRReporter readers already had the opportunity to be acquainted with the poetic revelations "Metamorphosis of Cities" that were presented in the rubric "From the neighbour’s library." Now we present an interview with the poet conducted by the translator of his book, Zdravka Mihaylova.

Besides being a poet and university lecturer, you are in charge of a theatrical workshop at the University of Cyprus, which has staged numerous performances at the professional level, both in Cyprus and abroad. In them folk culture stands out through a modern artistic expression. Tell us more about those activities and the cultural festival of the University of Cyprus, which you organize in the old building on Axiotea Street in Nicosia.

The theatrical workshop at the University of Cyprus was established years ago and its goal is to fill important gaps in the Cypriot theatrical space, to explore areas unexplored by professional theatre such as the works of medieval and Renaissance literature of Hellenism from the periphery, i.e. those written in dialects, such as Greek, Cretan and others. These works have been constantly and diligently explored from different angles. We try to utilize elements of tradition and folk rituals, which, as you know, have centuries-old roots in Mediterranean cultures and are rich in theatrical activities. In this sense, our performances are not planned in view of a number of performances. But if we believe that there is room to explore a text more deeply, the work on it continues.

During these fifteen years, we have staged only seven works and we have constantly continued to work on them, bringing changes and improvements. Actors often change too, as some young people leave and others come in their place. Essentially it comes to working up on the same text (something like a work in progress), which gives us the feeling that we increasingly extend our knowledge in the same area. This is something unique as our literature is a real mine from which we continually dig up new diamonds (diamonds of words). The most important thing in this adventure of drawing new knowledge is that our audience (that we have created due to the quality of our work) follows and encourages us, seeing each new version, the result of a different approach to the same work. There are viewers who have attended some of our performances more than five times, naturally over the course of the fifteen years since the Theatrical Workshop has existed.

What are the main accents of the Cultural Festival that each year takes place in the ancient Axiotea yard which houses the theatrical workshop?

Over time, the festival has expanded and become enriched, especially with concerts of selected quality music. This festival has its own specifics. On one hand, it is not interested in theatre formations that enjoy a noisy commercial success, in artists who respect the tastes of yet another "wider audience" or the "commercial Piazza" to put it another way; it is interested in artists who are accountable to their own art, who are consistent in their development, even if it often keeps them in marginal areas.

Our festival is thematically focused. The emphasis in our interests is on the Mediterranean culture and especially on its expression in the periphery, in more remote areas. Mainly the crossroads and impurities of culture capture our attention as well as the culture that is produced of idiomatic languages and dialects, because it is not deprived of individuality by the dominant culture in a country. This peculiarity is still typical of those areas that have not yet fallen under the norms. Therefore, our choice falls on a few "logs" or "lonely" artists, on the feeling of closeness, on formations that fit very well into the homelike atmosphere of our festival. The stage is actually located in the courtyard of a house of traditional architecture on Axiotea Street in the old part of Nicosia.

You have staged "Ballad of the Dead Brother'' and "The Bridge of Arta" - two motifs that are found in the oral tradition of all Balkan peoples. Publisher of "The Anthology of Balkan Poetry" (ed. "Friends of Andy magazine", 2006-2008) Christos Papoutsakis has even preferred the first of them as a motto that symbolizes the general expression of the Balkan soul. To what extent could Cyprus be considered part of the Balkans?

Before I answer let me say that I have really been systematically involved in the study of our folklore, both in my lectures at the University of Cyprus and in the activities of the theatrical workshop. However, only the adaptation of "The Bridge of Arta" ("Song of the Bridge" would be better) reached the stage. We have worked on many other stage adaptations ("Song of the Dead Brother", "Heliogeniti", "Haberdasher," "The Evil Mother", etc.), philologically and dramatically, but they have not been acted on stage. In every case, this study shows that regardless of how far Cyprus is from the Balkan Peninsula in terms of geography, spiritually and culturally it belongs to it as much as it belongs to the Levant. I am convinced that Cyprus’ strong relationship with the Balkan culture passes through its undeniable organic link with the Greek culture. This means that Crete, Cyprus and Rhodes belong to the Balkans as much as Greece.

You yourself are the author of a play, "The House", which was staged at the Michael Cacoyannis Foundation in Athens. In your theatre writing, critic Leanrdos Polenakis distinguishes some influences from Plato sneaking behind the seemingly ordinary but particularly complex dramaturgical structure. Advanced Pirandello’s technique is inserted in too, a game of opposing mirrors and endless reflections? What goal have you set by engaging the audience as a participant in the stage action?

I can say that the presence of Pirandello is quite deliberate (though not the result of preliminary intention). Just my theatrical education and talent, whatever it is, too early have passed through exploring the art of Pirandello and its charm. When I was a teenager, maybe in the third grade at high school, I was awarded the first prize for narrative in a literary contest at school and they rewarded me with a book with plays by Pirandello, which had just been translated into Greek. I read and reread them enchanted. By a happy coincidence, RIK (the Cyprus radio and television broadcaster) staged an avant-garde theatre play directed by Evi Gavriilidi at the same time; there were plays by Pirandello among the performances, which I saw as many times as I could. Therefore, I take for granted that, in the early period of my spiritual formation, Pirandello and of course, other important playwrights (Beckett, Pinter, Ionesco, Arabal and others) had a crucial influence on my orientations and on my theatre writing style.

As for the other part of your question (about the influence of Platonic ideas), it is not easy to give an answer. As a graduate of a good Philosophy School, such as that of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki at the time when I studied there (1972-1978), I am certainly familiar with Plato’s works. I even remember initially considering continuing to study philosophy when I had to choose the profile of specialization. But the lecturers at the Philosophy Schools did not inspire me then, unlike the lure of neo-Hellenists (especially G.P. Savidis but also D.N. Maronitis who was teaching Modern Greek poetry at that time). Therefore, I turned to Modern Greek literature that I combined with Theatre Studies and I have not repented of this choice. Later, Platonic ideas occupied my attention sometimes, either through my poetry or mainly through the study of other poets that had been engaged in dialogue with Platonic topics such as Cavafy. Thus, at the level of the architectonic form of the work, but with certain ideas presented in it, the knowledge of Plato probably had a "hypodermic" effect as an indispensable assistant.

You have also dealt with the relations between Cyprus and Spain in terms of their literary interaction. It is known that these relations have a long history and they are not limited to the commercial sphere alone. In the 14th century during the Lusignan era, the royal courts of Cyprus and Aragon, one of the most powerful Spanish kingdoms at that time, established closer relations. The most important dynastic marriage was between King Hugo’s son, Petros, and Eleanor, the daughter of the heir to the throne of Aragon. The marriage took place in 1353 and Petros was anointed King of Cyprus five years later. Eleonora of Aragon, already the Queen of Cyprus, played a crucial role in the political affairs of the island after King Petros passed away (1369), keeping power until 1380, when she returned to her homeland. How did the audience respond to the play about Eleonora that you staged with the theatrical workshop? Have you had the opportunity to visit Spain with it?

Our play on motives of the medieval "Cyprus Chronicle" with protagonists Peter I and Eleonora of Aragon was performed with great success, both in Cyprus and in many other European countries (Greece, Germany, France, England). It was scheduled twice to be performed in Spain but to no avail: the first time at the invitation of an unforgettable Catalan friend, Hellenist, Alexis-Eudald Sola, to be staged in Barcelona, and the second time at the proposal of university professor Moshos Morfakidis to be presented during a major neo-Hellenistic Congress in Granada. Ultimately, this idea was implemented with great success in April 2012 when, at the invitation of neo-Hellenist Claire Fotini Skandami, a large part of the work (that which refers to Eleonora) was presented in Barcelona. The play was a great success and our friends in Barcelona welcomed it with enthusiasm as we had taken care for the key moments of the play to be in the Catalan language so that the Catalan audience could get a taste of the turbulent life of this controversial and magnetic personality. Thus, Eleonora of Aragon, the Queen of Cyprus for a decade (1359-1369), returned to her homeland through a Cypriot work.