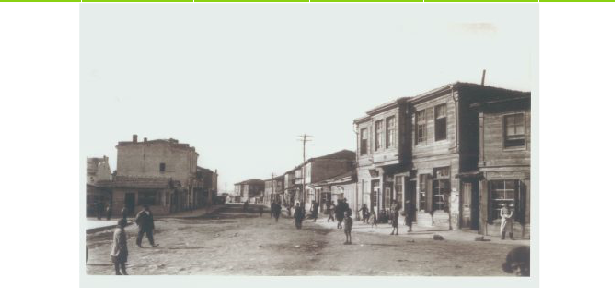

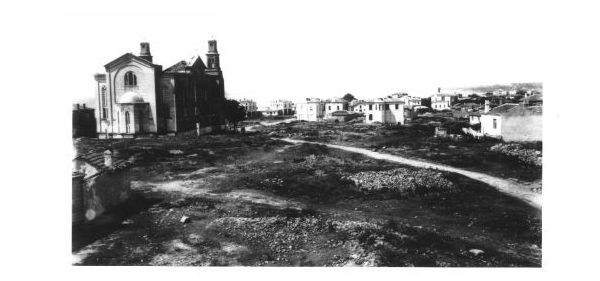

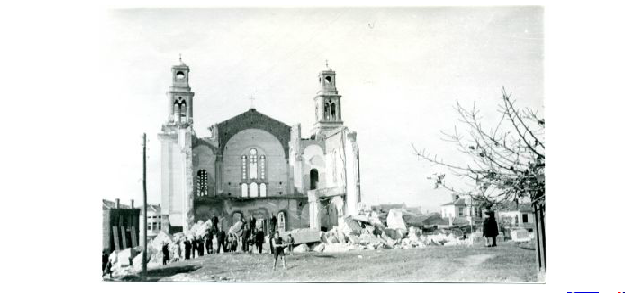

Anhialo (now Pomorie)

Anastasia Balezdrova

A month ago GRReporter published an interview with Greek historian and professor at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Iakovos Michailidis on the camp in Trikeri. In Bulgaria, the major explorer of the historical period when these developments took place is rector of Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridski" Prof. Ivan Ilchev. In his interview with GRReporter, he speaks not only about the events in Trikeri but also presents the overall picture of the Bulgarian-Greek relations in the early 20th century.

Professor Ivan Ilchev became Professor in Modern and Contemporary History of the Balkan Peoples in 1995, Dean of the Faculty of History in 2003 and he was elected Rector of Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridski" in 2007. He was a guest-professor at several American universities and the University of Chiba in Japan. Professor Ilchev has written 13 monographs, 67 scientific articles and papers, 40 book reviews, more than 150 scientific and popular articles and scenarios of 17 popular science films.

Professor Ivan Ilchev became Professor in Modern and Contemporary History of the Balkan Peoples in 1995, Dean of the Faculty of History in 2003 and he was elected Rector of Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridski" in 2007. He was a guest-professor at several American universities and the University of Chiba in Japan. Professor Ilchev has written 13 monographs, 67 scientific articles and papers, 40 book reviews, more than 150 scientific and popular articles and scenarios of 17 popular science films.

Mr. Ilchev, what was the fate of the Bulgarian populations in Greece in the period from the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire until the end of World War I?

The Bulgarian populations fell within the Kingdom of Greece following the signing of the peace Treaty of Bucharest. At that time, the Kingdom of Greece included the areas around Kostur, Lerin, Ber, Voden (now Edessa) and parts of the Thessaloniki area that were populated mainly by Bulgarians. Unfortunately, the politics that the Greek government pursued was not significantly different from the politics followed by the majority of the Balkan governments. The Greek troops captured the Bulgarian churches even upon entering this territory and the priests had to recognize the authority of the Patriarchate. Those who disagreed were removed from their posts and they emigrated. The Bulgarian liturgical books were burnt. The Bulgarian church trustees were disbanded and the Bulgarian schools were closed down. Actually, there was an immediate ban on teaching in Bulgarian. This caused the beginning of a wave of refugees, which did not abate for decades.

At the same time, the Greek immigrants arriving from the lands of Ottoman Turkey began to settle in these lands and the process continued during World War I. Greece was not involved in the war for three years. It was one of the last countries that intervened in it in 1917, when the government of Northern Greece, headed by Elefterios Venizelos and supported by the Entente, took power in the country.

Venizelos was one of the few Balkan political leaders who had a vision for the future. During the talks on the Balkan Union in 1911-1912, he insisted on predefining the future border between Bulgaria and Greece. He suggested that the border would pass along the lakes that are north of Thessaloniki. The Bulgarian delegates objected that this border would leave numerous Bulgarian populations in the area of Kostur, in Voden, under Greek rule. He replied that there would be many Bulgarians in the area but Bulgaria would add to its territory Eastern and Western Thrace

that was the home to numerous Greek populations. According to him, a gradual exchange of populations between the two countries could clear the process. His motives were not so altruistic. He actually wanted to have an ally or at least a neutral country behind him in a subsequent conflict with Turkey on the fate of Western Anatolia and Istanbul.

The disagreement with such a border on the part of the Bulgarian negotiators initiated the negotiations between Serbia and Greece that led to an alliance against Bulgaria. Therefore, to a considerable extent, Bulgaria itself is to blame for what happened in those years.

We can talk about two periods after World War I until 1923. The first period is from the end of the war to 1922, when the peace Treaty of Sevres gave Eastern Thrace to Greece, Western Thrace was temporarily under French control at first but actually, all knew that it would join Greece to provide the necessary corridor to Eastern Thrace and so it happened. Then the process that had started even during the Balkan wars spread to Western Thrace where the transfer of endless caravans of refugees from there to Bulgaria began.

Turks had already taken care of Eastern Thrace as early as 1913 when, within three months, they had chased away all Bulgarian and Greek populations from the area and it had become Turkish in terms of population.

In Eastern Thrace, the population was divided roughly into three groups before the Balkan war, namely 1/3 Bulgarians, 1/3 Greeks, 1/3 Turks. After the defeat of Bulgaria in the Second Balkan War, when Turkey seized eastern Thrace again, it did not make a substantial difference between Bulgarians and Greeks - it chased away the two ethnic groups and therefore, not more than 1,500 Bulgarians remained in Eastern Thrace a year after the end of the Second Balkan War.

The situation of the areas where a small number of Bulgarians lived significantly complicated after the defeat of Greece in the war with Turkey in 1919-1923. In the last months of the war when it became clear that Greece would lose it and after the signing of the peace Treaty of Lausanne, hundreds of thousands of Greeks emigrated from western Asia Minor, where they had been living for thousands of years, from the time of the Trojan War, and went to Greece. The Greek government tried to settle these migrants among the Bulgarian populations. The goal, of course, was clear, namely to change the ethnic composition of the area and it really changed. After 1923, the majority of the populations everywhere in today's Greek Macedonia and Western Thrace were already Greek. An additional tool to remove the Bulgarian populations was the Mollov-Kafandaris Agreement that provides for an exchange of populations.

Accordingly, what was the fate of the Greek populations in Bulgaria during the same period?

In Bulgaria, there has always been a relatively smaller number of Greeks than Bulgarians in Greece. The liberation found around 60-70 thousand Greeks and there was a process of constant emigration from Greece to Bulgaria. The Greeks in Bulgaria lived in several enclaves. One was the area of Plovdiv and Stanimaka, the second was the Black Sea coast and the third the area around today's Topolovgrad and Elhovo.

The anti-Greek pogroms in 1906 gave a strong momentum of Greek emigration from Bulgaria. There were no anti-Jewish pogroms in Bulgaria but anti-Greek, unfortunately. In 1906, the anti-Greek pogroms totally burnt the booming Greek city of Anhialo at that time, now Pomorie.

Photos: zarariswines.gr/history.html

Photos: zarariswines.gr/history.html

The relations between Bulgaria and Greece were never good just because of the history of church and cultural relations, then followed the struggles in Macedonia and especially what happened in 1905, when the Greek andartes, guerrillas, attacked the Bulgarian village of Zagorichane, in the region of Kostur, where Dimitar Blagoev was born, and killed several dozens of people, including men, women and children. This provoked anti-Greek demonstrations in Bulgaria that occurred over several months in the summer of 1906.

Varna citizens refused to accept the Greek bishop sent by the Ecumenical Patriarchate. According to the decisions of the Treaty of Berlin, the Greek parishes in Varna and Stanimaka remained subject to the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The Bulgarians seized the property of the Greek Church in Varna and expelled the bishop. In Plovdiv, they conquered the Greek churches in the old city and turned them into Bulgarian ones. The most significant conflict was in Anhialo, where it is not clear even to this day, who fired the first shot. However, the Greeks from the city barricaded themselves behind the walls of the monastery that was in the outskirts of the village, a house was on fire during the fight, there was a wind and the whole city was on fire too. It was a wooden city and it actually burnt.

Photos: zarariswines.gr/history.html

It was after these conflicts that a strong wave of emigration started from Bulgaria to Greece.

There are no innocent people in both countries, but I have always been opposed to measuring who was more brutal, uncivilized and uncultured. No matter who behaved in that way, it is important that the manners of both countries were uncivilized and uncultured, and that they oppressed their subjects, who did not belong to the dominant nationality.

More than a century later, how do we perceive the Carnegie survey? Can it be accepted as a document that objectively presented the events? What is your response to the allegations that some of the participants in the commission were paid?

The participants in the Carnegie survey presented in their surveys what they had seen, the documents to which they had had access. Their situation was very difficult because in fact, Greece did not allow them to interview the participants in the wars on its territory nor to see the Bulgarian villages burnt, the Serbs did not accept them on Serbian territory either. What they were able to see was mostly Eastern Thrace because the Turks allowed them to, and the lands that joined Bulgaria after the Balkan wars. They talked mostly with refugees. When talking to refugees, clearly each individual story is evocative but that does not mean it is not true. Therefore, some of the pages in the Carnegie survey are very emotional.

Actually, the Carnegie survey wants to allocate the balance of guilt among the participants. They rather say that all countries behaved in an uncultured and uncivilized manner in this conflict. If they speak about a balance of guilt, they believe that the behaviour of the Greek and Serbian guerrillas was much worse than that of the Bulgarian rebels in the war.

As to whether they could have been bribed, this is a ridiculous question. We consider things from the viewpoint at the beginning of the 21st century. The participants in the Carnegie survey were professionals, well positioned in the professional circles and nobody even thought of bribing them. Definitely, they were not bribed. They were not that kind of people.

It is another issue that when the Carnegie survey was released the Bulgarian government tried to obtain as many copies of the book as possible to use them as a propaganda weapon but to no avail because World War I began and the world was no longer interested in the previous conflict but in the new one. Either way, their personal honesty cannot be questioned.

What exactly happened on the island of Trikeri? Who were the people interned there, what were the charges against them and what was their fate?

Trikeri island has a lamentable reputation in Bulgaria, because soldiers during the Second Balkan War and Bulgarians from Aegean Macedonia, who were active until the wars or in the church or the national liberation movement, were taken and captured there.

The island was actually a concentration camp without wire fences, it did not need them because it is a small island with no natural sources of water. It is not clear how many people died there but probably hundreds of the several thousand Bulgarians who were taken there. They died primarily from diseases caused by the climate to which they were unaccustomed, mainly from malaria, and from the diet, which was not favourable to them. I have not heard anything about deliberate murders, I do not think it has been proven that prisoners had been shot. Rather, the conditions were so bad that many of the people interned there died.

What measures did Bulgaria take against the Greek populations in the coastal cities? Was there internment of people similar to that committed against the Bulgarians in Greece?

I have already mentioned the Greek populations in the coastal cities. There were no interned people. There are no such conditions in Bulgaria, for interning people in places such as the island of Trikeri. There were people who were declared persona non grata, who had to leave Bulgaria, but no people were interned.

We have recently witnessed a new rise of extreme nationalism that is threatening the stability in various regions of the Balkans. What are the lessons that the modern residents of the Balkan countries should learn from this period?

A thinker says that nationalism is as a fireplace covered with ash - when someone stirs up the ashes, the coals show from below. Unfortunately, in many cases, the representatives of the dominant race of a particular Balkan country are hardly aware of the attitudes of the minorities, finding it difficult to understand them.

Furthermore, the Balkans, I do not know how many of your readers realize this, are the region of Europe with the greatest diversity of cultures, religions and languages. No other region in Europe with an area of about 500,000 square kilometres is inhabited by at least eight nations with over 1 million people, including Romanians, Bulgarians, Turks, Greeks, Albanians, Serbs, Bosniaks, Croats. There are at least five more nations of between half and one million people. On these 500,000 square kilometres, we have followers of the two denominations of Islam, namely Sunni and Shia, we have Christians too - Orthodox, Catholics and Protestants as well as Judaists. The people on this territory write in three alphabets, namely in Greek, Cyrillic and Latin. On this territory, there were three separate calendars until the early 20th century.

It is extremely difficult to find an ethnically pure territory in the Balkans. Where there are ethnically pure territories, they typically are the result of ethnic cleansing, be it for a shorter or longer period. There are pure areas at the heart of today's Serbia but it was the home to many Turks until the 1920s who were expelled from the church. There are pure areas in some regions of Greece but many Albanians lived there before. Not to mention Bulgaria - there are virtually no clean territories from an ethnic point of view, there have always been minorities in it. So, unfortunately, nationalism in the Balkans has many dry trees that can ignite a conflict.

I do not know if people realize that sometimes a very small conflict could escalate into confrontation in which tens of thousands may lose their lives. Do not forget that the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina began with a conflict at a wedding. Therefore, when the situation is tense we must be very careful.

I am not entirely sure that the Balkan nations have learnt lessons from what has happened. Some incidents in recent years make me think that they have not at all learnt these lessons. New attitudes are rising, new radical groups are rising, a new radical thinking of disregarding the other is rising. By the way, in all the Balkan countries and in Western Europe, this finds expression in the so-called soccer fans who are present in the Balkans as well and who turn out to be one of the ‘reservoirs’ of the armed conflict in Yugoslavia, Macedonia, etc.

Therefore, I am moderately optimistic about the future of the Balkans. I believe that the accession to the European Union has helped the countries that are in it, namely Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Croatia, Slovenia, as willing or not, these countries have to observe certain rules that have not been established in the Balkans but that have proven to make sense in Western Europe.