Initial photo: Aris Messinis/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

The concept that the Balkans are the door of the East to the West is not new. However, it gained some new dynamic around the Greek crisis and the fact that six years after its eruption the country is still meandering between the old, which is unwilling to go away, and the new, the coming of which is not wanted by everyone.

Similarly - as a country that is in continuous transition from East to West, is how the professor of political science at Yale University, Stathis Kalyvas, describes Greece in his latest book entitled, Modern Greece: What everyone needs to know.

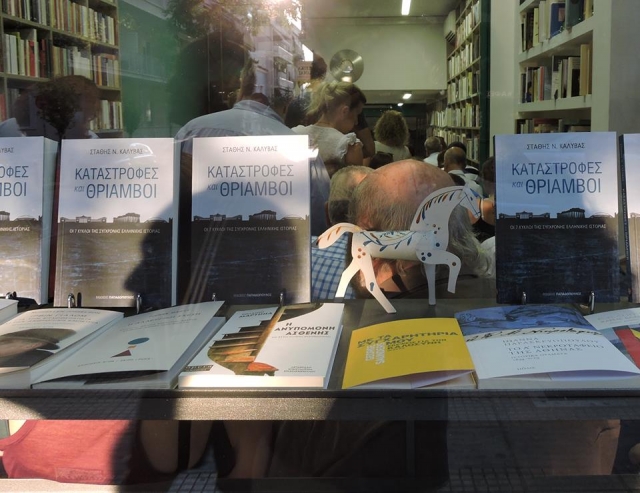

In it, Kalyvas scrutinises the history of the modern Greek state since the beginning of the 1821 Greek War of Independence until today, dividing it into seven rounds. "What characterises all these rounds is that they set out with a vision, which is mighty and hard to achieve. Down the road, Greece begs for help overseas and ends up receiving it. And the result of all this transition is pushing the country one step up," explains Kalyvas during the presentation of his book in the Athens Pleiades bookstore.

Photo: Pleiades bookshop

But why do Greek crises always ultimately make it to the international stage and trigger interventions by the international community? "The answer is complex, but is primarily linked to the fact that the country's endeavours have always been associated with major international bets," says the author.

In the preface, he states that the aims Greece was targeting during its development were linked to the organisation of society, the building up of its statehood, the democratization of its political institutions and the acceleration of its economy. "They are all endeavours, which stand at the core of modernisation as a concept. Their interpretation shows the big challenges of grafting Western institutions onto countries that pursued neither the historical, nor the cultural development of the West. At the same time it offers a brief description of the challenges faced by the developing world's attempts to reach modernity. From this perspective, I believe that Greece's history is a matter of both special and wider interest."

The gist of the seven rounds was presented in a fascinating dialogue between the author and the writer Petros Tatsopoulos. The first round begins with the creation of the modern Greek state in 1828 and runs through the polemics between rebels, who participated in the War of Independence, and the Greek nationals who got educated in Western countries – and were trying to borrow the European model of governance.

"Lord Byron, who was tasked to deliver the loan granted to Greece, had to decide who was worth giving the money to. And the looks of the two sides in this stand-off speak volumes: on the one side were the moustachioed ones, and on the other were the bespectacled ones," says Kalyvas. After much hesitation, Byron gave the cash to the Western graduates, but it wasn't ultimately used for the modernisation of the downtrodden and impoverished former Ottoman province.

The second round began when the loan was spent, but Greece was still struggling to adopt the standards of a Western country. The same period is connected with the emergence of Greek irredentism embodied in the Big Idea (Megali Idea). The already established state was far from meeting even the minimum standards, and its relations with the West were still fraught, despite the West's tendency to admire the achievements of ancient Greece.

Photo: Pleiades bookshop

The third round marks the first genuine attempt by Greece to join the West. Under the rule of Prime Minister Charilaos Trikoupis, the country raised large loans and invested heavily in its infrastructure. Greece lost the 1897 war and 1 million of its folk were compelled to emigrate mostly to the United States to seek a livelihood and a better life.

The sovereign bankruptcy, which went down in history with the famous "Unfortunately, we went bust" announced by Tricoupis in parliament, however, laid the foundations of the subsequent economic revival. It is worth noting that this period saw the rebuilding of the entire state machine. Both Kalyvas and Tatsopoulos emphasised that the Eleftherios Venizelos, known as a reformer who steered Greece up to the standards of the modern bourgeois state, had largely found the foundation for his subsequent endeavours already in place.

Venizelos' era, known for his reform agenda, is placed at the beginning of the fourth round of Greek modern history. But the political situation was often shaken by military movements, dictatorships and, of course, the two world wars.

During WW2 Greece became the first front of the Cold War. Although the view enshrined in historical literature is that the Greek civil war began in 1946, Tatsopoulos pointed out that in fact it happened way back, in 1943, during the German occupation. "Members of the Greek Liberation Front – the military arm of the Greek Communist Party – conducted purges against their political opponents since then. The subsequent Treaty of Varkiza, signed in 1945, was breached by both the communists, many of whom did not surrender their weapons, and the authorities. But the important thing to note is that the Civil War only lasted as short as it did because of the conflict between Tito and Stalin. Had it not occurred, and had the Greek Communists not rallied openly behind Stalin, the conflict could have lingered even into the 1960s," said Petros Tatsopoulos.

Photo: Pleiades bookshop

"After it finished, a period of rapid economic development was set off, described as the 'Greek economic miracle'. At that time, Greece ranked second in these terms after Japan," said Stathis Kalyvas.

We are already in the fifth round, which is marked, among other things, by the military junta (1967-1974), the events of the Athens Polytechnic and the restoration of democratic order in the country. Tatsopoulos made an interesting remark that during the seven-year dictatorship of the colonels, society's resistance against it was insignificant. "By the end of it, we had heard the names of a few individuals, e.g. Alekos Panagoulis. Then suddenly the 'fighters' swarmed up, and it was strange how the junta had not collapsed earlier as a result of their actions." He added that the entire Eastern bloc showed great tolerance, if not support, for the perpetrators of the military coup and their 7-year rule.

For Kalyvas, the military dictatorship is the time when Greek populism in its current shape emerged. "The fact that the coup was carried out by colonels who prevailed over the generals, creates a feeling of an institutional weakness," he said.

Both writers shared the opinion that the junta was a consequence of the inability of the political forces in Greece to democratize the country.

After its demise, the country began to recover, and in 1981 became a member of the European Economic Community. Obviously not because it met all economic conditions, but by dint of a political decision.

Greek society had meanwhile become quite different. A middle-class had emerged, people were living mostly in the cities, the younger ones had become open to modern-day achievements. But populism was growing no less, and it prevailed after PASOK won the 1981 elections. Greece received enormous aid and subsidies from the EEC, but failed to use them appropriately. According to Kalyvas, "the only period, during which the indiscriminate spending was limited, was after 1997 until Greece's accession to the Eurozone: it is associated precisely with the run-up to the accession."

Greece's participation in the common European currency is an opportunity for change and reform. However, the government of Costas Simitis failed in its attempt to reform the pension system, and the government of Kostas Karamanlis did not take advantage of lower interest rates on lending to channel funds into bringing the economy up to scratch. A large influx of economic migrants, mainly from the neighbouring countries, took place, but the country missed a unique opportunity to renew itself, despite its atrocious demographics.

This is how it got bogged down in the economic crisis, and Stathis Kalyvas scrutinises the reasons for it in the sixth round. Apart from the economic aspect of the problem – the bloated public sector, the reluctance to carry out reforms – he cites nationalism as another underlying reason for the crisis. "European integration is a threat to nation states. Therefore, for the opponents of the bailout memorandum, the imposition of European policies constitutes a violation of state sovereignty."

In the seventh round, Kalyvas describes what Greece's future could be after the crisis. In conclusion, the author argues that "in the end of the day, Greece hasn't done so badly." He cites a quote from Donna Tartt's Goldfinch, which reads: "Maybe sometimes you do everything wrong and at the end everything turns out the right way?" The quote features as the motto of the book. At the premiere, Kalyvas argued: "Greece has enormous economic opportunities, which should be released if it is to find its way out of the crisis. This is possible, but has not happened so far for political reasons." Kalyvas listed the necessary prerequisites for this: political stability, solid governance, which will carry out the necessary reforms and will unleash production forces and also generate a feeling among the public that things will gradually improve.

Unlike Kalyvas, Petros Tatsopoulos said he was pessimistic about the happy turnout to this open end of the seventh round. Throughout the discussion, he kept slamming the political and government behaviour of SYRIZA, and expressed doubts that the party is capable of implementing the agreement with creditors it signed on 13 July. Commenting on the bickering within the party and the open calls by some hardliners that Tsipras should suspend the negotiations on a third bailout package until the party's in-house fracas is resolved, Tatsopoulos made an analogy with Lord Byron and the letters he received in Kefalonia from the candidates to take over the loan for the newly-established Greek country. "Some things have not changed much since," said the writer.