Pictures www.kathimerini.gr

The oldest known photograph of Thessaloniki welcomes readers of the new book by Aleka Karadimou-Gerolimpou. It was taken in 1863 in the area of Bestsinar in the western part of the city and depicts the sea wall and the tower of the pier. The picture was taken by Austrian photographer Dr Josef Szekely, who visited the city as part of an expedition to the Balkans of Ottomanist Johan Georg von Hahn.

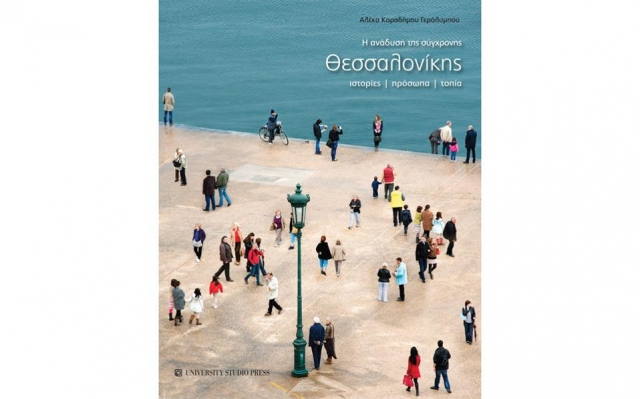

Overgrown with more or less impressive minarets, this pre-modern Thessaloniki emitted something medieval and the eyes followed a long stretch of walls with characteristic serrated edges. Everything, or almost everything, started here, and then we got to the more intimate city of the 20th and 21st century. And this is the "journey" which architect and professor emeritus of the University of Thessaloniki Aleka Gerolimpou depicts in her new project entitled "The emergence of modern Thessaloniki: stories, people, landscapes," which is published by University Studio Press.

It contains 12 parts which selectively follow the major changes in Thessaloniki since 1870 (which is considered to be the beginning of the modern period) to the 21st century. Some of the texts have been published before, but are generally unknown to the general public.

In the second half of the book, the author's work is directed towards individuals in the history of the architecture of the city (the majority of whom have been more or less completely ignored by modern bibliography). Also, a mood of a novel dominates throughout the second half of the book – maybe because the lives of these individuals actually resembled novels. These include the French military engineer Joseph Plemper (1866-1947) who spent much of his life in the colonies (Indochina, Madagascar, Senegal, Sudan, etc.) and came to Thessaloniki in 1915. Plemper loved Greece and made Thessaloniki his second homeland, starting his career of an architect here at the age of 52, as part of the recovery of the city after the fire of 1917.

Thanks to Aleka Gerolimpou, non-specialists will have the opportunity to learn about significant people of Thessaloniki between the wars who, due to their work and passion, left traces on the face of the city, such as Anargiros Dimitrakopoulos (1885 - 1966), an engineer and a senior civil servant who is completely forgotten today, as well as Joseph Nehama (1881 - 1971), who was part of the Thessaloniki Jewish intelligentsia. Nehama never concealed his disappointment since he thought that the Greek state treated the Jews as second-class citizens (especially in the late 20s). A separate chapter is dedicated to Alexandros Papanastasiou (1876 - 1936), the inspirer of the new city planning and the establishment of the university, mainly as a transport minister in the government of Venizelos.

This is a book which offers both an academic and amateur look at the bibliography of modern Thessaloniki, by a woman who knows and loves this city more than most Greeks.