The three best-preserved parts of the Antikythera Mechanism

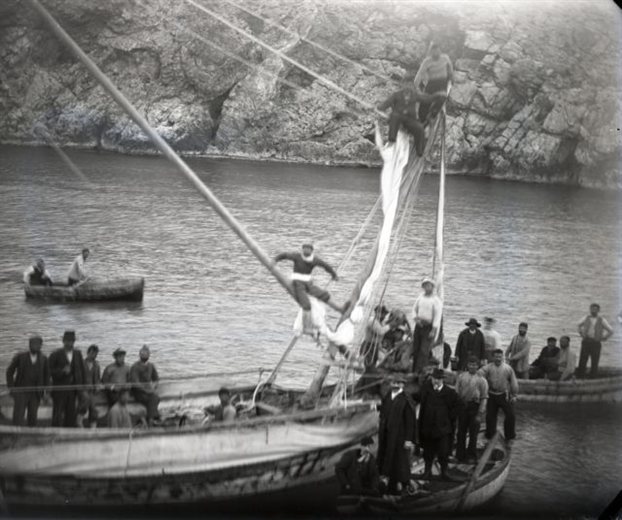

In May 1900 traditional sponge divers from Symi Island stopped in Antikythera. By force, due to one of the, frequent for this part of the Ionian Sea, storms. When the sea had calmed down, one of them – Ilias Likopandis dived in. But instead of sponges, at a depth of approximately 50 metres, he found the remains of a wrecked ship. Around it he saw marble statues and bronze figures. When he came back up to the surface, he held as evidence a bronze arm.

Six months passed after the discovery before the diver managed to contact the then minister of education and archaeologist by profession, Spiridon Stais. Only then did the organization of an action for taking out the valuable cargo begin, with the help of the Royal Navy.

More than a century later, the treasures, found on the ship, are shown together for the first time at the exhibition of the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Meanwhile they have gained world fame not only because of the works of art the ship had carried aboard. The most valuable discovery is the mysterious “Antikythera Mechanism”, which its first discoverer, Derek J. de Solla Price, defines as “the most ancient example of science technology, which has survived until today and which changes our ideas about the ancient Greek technology.”

378 items are on show at the exhibition entitled "THE ANTIKYTHERA SHIPWRECK The ship - the treasures - the Mechanism”. Among them one can also see objects found during the second archaeological research in 1976, in which Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s ship, “Calypso”, took part.

Statues and luxury vessels, ornaments, coins, glassware, clay pots and bronze vessels, parts of a bed. Parts of the ship itself, leftovers of food and, of course, the Mechanism, represent the voyage of the unfortunate ship, that had sunk in 50 – 60 BC. An era, in which trade shipping and sea transportation of works of art from the East to the West had reached their zenith. According to experts, the cargo belongs mostly to the Hellenistic period (the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 1st century BC), with one exception: the finely made bronze statue of the so called "Antikythera Youth" created in the 4th century BC.

Antikythera Mechanism

Astrolabe? Planetarium? Astronomic clock? Or maybe something else? Months after the operation for taking out the cargo, the participants start to realize that the quadrangular box they had taken out together with the works of art was something very specific.

Today, scientists know that the Antikythera Mechanism, which was created in the 2nd century BC, not only is the most complicated mechanism of ancient times, but nothing has been found to resemble it over the next 1,300 years. It is made of cogwheels, measuring lines, axes and pointers. On the basis of the then known astronomic principles, it was used to define the exact positions of the Sun and the Moon, as well as perhaps of other planets. The mechanism was used to count the Moon’s phases, to foresee eclipses and to define the date of the games in Olympia, Nemea, Delphi and the Isthmus of Corinth.

It was also used for presentation and teaching of astronomic phenomena. Instructions for use were found on the mechanism and its case. “Antikythera Mechanism” is an analog computer. Its meaning for the development of technology is as great as the Acropolis is to the development of architecture”, the member of the International Group for the Study of the Antikythera Mechanism, astronomer Yannis Siridakis, asserts. It is not yet known who the creator of the Mechanism was. Experts hesitate between Posidonius of Apamea in Asia Minor, or the great mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse.

The exhibition

The first part of the exhibition is called “The adventure of discovery: the birth of underwater archaeology”. It represents all efforts to find the wrecked ship, the ensuing restoration, press announcements, and all state documents of each era.

“The ship, its capacity and its crew” is the name of the second part. It represents parts of the ship’s body as well as its external lead cover, drainpipes, weights for depth-measurement and for defining sea-floor relief. The remains of the ship and its cargo show that it had been loaded with an estimated capacity of 300 tons. In Ancient Greece these ships had been called “olkas” and in Latin "navis oneraria". The objects found, as for example vases and games show the habits of the people on board.

In the third section visitors can find the “Ship’s voyage and its cargo”. The above described objects show not only the aesthetics of the potential buyers, but the new practice in the history of Western civilization – trade with works of art. The study of the cargo helps us understand sea trade and movement of Greek works of art at the end of the Hellenistic period towards the Roman Empire.

The fourth and the last part, which includes one third of the entire exhibition, is devoted to the Antikythera Mechanism. 82 remaining fragments are shown, including the three best-preserved parts. Also, parts of the studies of the Mechanism are presented, drafts, radiographies, digital reconstructions and models, accompanied by the interpretations of scientists and experts, made in the century after it had been found. The exhibition ends with a projection of a short 3D documentary film by Philippe Nicolet.

Place: The National Archaeological Museum, 1 Tositsa Street, Athens.

The exhibition will last until 28 April 2013. More pictures can be seen in our photoreportage.